On Wagashi, Barriers, and Boundaries

Reflections on both traditional Japanese pastries and the current task of travel writing

Apologies to the faithful readers: I meant to have this one up this time last week, as April’s essay. I’m in rural Tuscany for the spring, only about halfway on the grid, and my laptop charger broke my second week here. This is a long-format piece I’ve been working on for a while now—and it surely did take a lot of time and reworking of this essay, as I’m covering a bit more than just food with this one—and there will be a second, shorter piece later this month, likely containing some snippets from my time here in Italy.

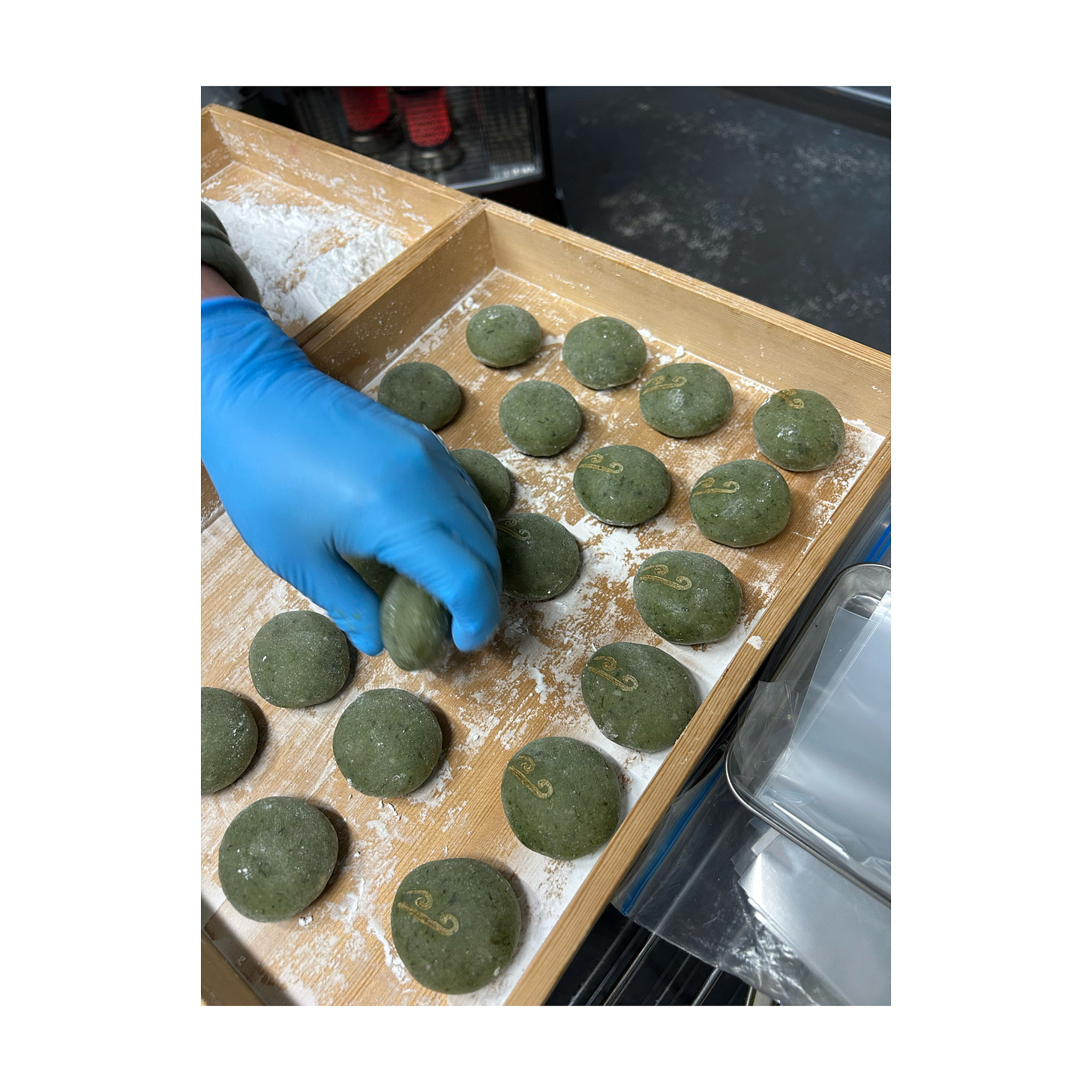

A recipe for Warabi Mochi, according to my notes: combine 50 grams black Warabi starch powder, 100 grams of wet sugar, and 250 grams of water in a pot over a small fire. Stir. Warabi will melt, get gloopy. Stir constantly, til black and shiny, about 5 to 8 minutes, then pour out onto a Kinako-lined sheet tray. While still hot, portion into 10 gram pieces and wrap around 20 to 25 gram portions of red bean & black sugar paste.

Simple enough, if, for one, you can track down the temperamental powdered starch of the bracken fern Warabi, figure out what wet sugar is (glucose or another invert sugar?), source Kinako, and through a good amount of trial and error, and remember just how warm the pieces need to be to wrap them around the bean paste before they stiffen up and become unusable.

Wagashi, the Japanese art of confectionaries, is a world unto itself in a country that’s already made up of niche arts and crafts. These small, intricate handheld pastries meant to be served with tea include a few staples you’re probably familiar with, namely various rice flour mochis, but also entire other subcategories of sweets made from greens and ferns, jellies made from seaweed, flavorings made from underripe fruit, and a wide array of pastes made from sweetened beans. For a western pastry chef like myself, it’s endlessly fascinating–and tricky to understand. It takes about as much unlearning as it does learning: this is not about butter temperature or gluten formation, but rather the congealing properties of foraged starches and yam powders, the density and water content of beans, the power of steam. And it’s about something more than that altogether, a delicacy and finesse and care that is inherent in most every craft in the country.

My notes from my two days of learning Wagashi are hardly legible. Less of a written record and more of a poorly drawn map or sketch, the kind I would draw as a child on a kids menus and church pamphlets, with scribbles for names and arrows going in all directions connecting seemingly disparate points.

One of the better pieces of travel writing I’ve read in the last few years is “How Things Disappear: A Travel Writer’s Pilgrimage” by

. It’s understated, hardly a guide at all on where to visit and what to do and more of a study of the current state of travel and travel writing as a whole. Curious to see if Estepa, a tiny, relatively unheard of town in southern Spain that Rick Steves wrote about long ago was still worth visiting, Wilson heads there on his own with no itinerary in mind. “I made a travel writer’s pilgrimage,” writes Wilson; “I’m still not exactly sure why.”Wilson wants to know what it is about this village that made Steves adore it above all others in the region. And, it seems to me, he’s after more than that: he wants to see what in the travel genre is still worth holding onto. It’s a genre that doesn’t hold the same sway as it used to, a product of the simultaneous expansion and simplification of the medium in the digital age. Guidebooks and long format articles have been funneled into bucket lists and Instagram reels; at the same time, a sometimes excellent, sometimes not array of TV shows have emerged in the post Bourdain era, most of them using food as the lens into another place and culture. Long format travel writing, on the other hand, hardly exists in the same way.

Nor should it, perhaps, at least in all the same ways it used to. There was an unstated premise to much of the genre which deserved interrogation, a premise of unlimited access and belonging. In the modern technological world, borders have largely collapsed; one can work from anywhere, with proper WIFI; credit card points unlock new getaways; social media distills the real roller coaster of foreign travel into picture perfect snapshots. In short: the world is your oyster; but that’s a dangerous premise when a city like Kyoto finds itself overrun by tourism every year, or the prices of rent in Oaxaca skyrocket and locals can no longer afford it.

Still, something is being lost without good travel writing, which can serve to celebrate local voices and producers and preserve the magic of places big and small. I’ll quote Wilson in full here from what is for me the is a particularly poignant paragraph of his essay:

“More than a genre of writing is being lost by our current era of corporate consolidation. I know in my small corner of the world, I’ve tried my best to amplify voices that were outside of entrenched media structures. But legacy media continues to cut corners as it tries to wring more from underpaid work.”

These words echo in my head in a month where Trump threatens to cut off funding for NPR and PBS. Good travel writing, like all good media, is more than just the content is it comprised of. It’s a way of seeing and listening—a reminder of not just where to travel but how to do it the right way.

Wilson found himself in a small Spanish village where there was nothing much to do but spend a day as locals do, at least when they are not working: he joins a local Carnival parade, he wanders into a bar and drinks beer with locals. It’s local life you experience in places like Estepa, and there’s beauty in this. Yet, I found myself in a mountainous Japanese valley that was being pelted with snow daily and where locals, already working wild hours because this is just what happens in Japan, were spending their down time shoveling snow constantly so they could get their cars out of their driveways. There were no town celebrations, at least on the surface: winter in these mountains is tough sledding.

I had just left a gig making pizza in a nearby area of Japan because I got a concussion and couldn’t deal with the noise and stress of a busy kitchen day after day. Not ready to leave Japan altogether, I thought I’d head back to the towns where I spent last spring cooking. But the staff at the restaurant I previously staged at, Satoyama Jujo, were too busy navigating the snowfall themselves to come thirty minutes out of their way to pick me up. My hotel was near the top of the mountain. It took an hour to walk down the road via a non-existent, icy shoulder, to get to the next town. I was, in short, stuck on top of a mountain for a week while the snow fell, foot by foot, day after day.

The one opportunity I had set up was a two-day stage with a master of Wagashi who lived a few towns over. A true master of the craft, a quiet and peaceful man named Baba Hidetake who moved from the city to the countryside when he learned he had heart disease. Seeking a slower pace of life while still wanting to make sweets, he built out a small but fully equipped pastry kitchen in his basement, where he makes some of the most sought after sweets in Japan and ships them to tea stores around the country. I was aware of him because the chefs at Satoyama Jujo would call him for advice on their desserts: how do I use this roasted soybean flour? Is there anything I should know about this specific varietal of hokkaido red beans?

Baba Hidetake San is a quiet, studious man who works in solitude and drinks tea and is intent on executing all the intricacies of his craft to his best ability. He is also a joyful man, quick to smile when I made many mistakes trying to replicate his processes, gentle and kind in how he would show me how to do things the right way, and eager to chuckle alongside me when the Google Translate algorithm churned out something silly.

The core of much of his work centers around beans. He showed me two varieties of small red beans in my first hour with him: one hardy variety from Hokkaido, dark and brilliantly shiny, and a lighter, smaller variety from the more temperate fields around Kyoto. The latter had more flavor, in his mind, and was also softer, not requiring an overnight soak. A few things I transcribed about cooking the beans: to leach the bitterness, cover the beans in water and bring to a boil, then immediately add the same amount of cold water to them. Strain about ⅔ of the water, add cold water to top, and repeat this process–a process called “hita-hita”, or perhaps this is just a general phrase about going slowly and gently– twice more to leach bitterness. On the last boil, turn off the heat and add cold water and do not strain: rather, let sit for an hour, then strain, then wash the pot really well, which apparently improves the color of the bean. Then, finally, you can cook the bean, under a weight, one that fits the pot perfectly of course, over medium heat for about an hour. And then? There’s a whole different process on day two for turning the cooked beans into a concentrated bean paste.

I feel like a foreigner constantly while traveling, but usually rely on kitchens to feel more at home. Cooking styles may differ all over, but there is at least a shared lexicon of flavors and techniques and work ethic, especially in the modern age where chefs in Europe are drawing on Asian cooking methods, Americans are turning their eye to some of the African ingredients and techniques that form the foundation of southern cooking, and so on. But this style of cooking was so niche, so foreign, that I was a fish out of water. Watching the way Baba Hidetake San moved, and pulled out ingredients I had never heard of, and transformed the ones I did know in ways I had never conceived of was mesmerizing and confounding all at once.

Wagashi require a delicate touch. Wrapping dough around soft pastes without smushing them, picking up tiny and fragile pieces of various pastes, forming the shape in just the right way. Our first pastry was a green (unripe) peach pastry, an annual delicacy for Girls Day in early spring. Green peach extract gets mixed into a white bean paste, which is formed into small balls that get a mochi coating of both rice and wheat wrapped around them, before being shaped into the form of a peach. My own hands, usually capable when it comes to these small intricate tasks, pushed the form into some sort of blunt, blockish peach—but the results, still, were remarkably delicious.

We stopped each day for an hour for lunch. He would prepare it–I was not allowed to help–and I would go wait in what he called “Brennan’s Waiting Room”, an office of sorts upstairs with a couch and table and many books and notepads littered about. I would sit there for twenty minutes while I poured over my notes, trying to make sense of them, and then he would bring a bowl of food for me. The first day he ate with me; the second, he left me a rice bowl and headed back downstairs.

It was extremely kind. It was also a reinforcement of the same wall I kept coming up against as I aimed to dig past surface level tourism in Japan, one where I was shown an incredible amount of generosity but rarely invited into one’s private life. I was learning that at least in this corner of Japan, in this wildly snowy, work-focused time of year, the longer I spent here the more I was feeling like an outsider. As well I should in some ways: in a country that’s increasingly overrun with tourism, daily rural life needs to go on here, away from the prying eye, someway, somehow.

Additionally, he picked me up and dropped me off both days, a forty five minute drive each way, despite me telling him I could rent a car. I would ask him a handful of questions at the beginning of each drive but between his quiet demeanor and our language barrier silence would soon overtake us. But the act of him ferrying me to and fro–it was, again, incredibly generous, especially when the roads were getting snowier and snowier.

That’s the crux of it, really: I may have felt like a burden, but he was doing this out of the kindness of his heart and a desire to pass along his knowledge. When I asked him over Google Translate if the younger generations of Japan were making Wagashi, he told me he wondered if the tradition was dying out little by little. Western pastries are beloved in Japan these days, and only a small percentage of young chefs want to devote themselves to the intricate, time-consuming, seemingly archaic craft of Wagashi.

The future, of course, doesn’t require Wagashi: it is a niche luxury, a sweet treat that compliments tea. And more likely than not it will at least partially fade in popularity as Western foods gain a further following in the East. It’s interesting to consider what we need and don’t need in food moving forward, when the world seems to be tearing at the seams. Travel writing, too, isn’t an absolute necessity either–and one could ask themselves the same thing about the concept of travel at large.

“Given the genre’s history of cultural voyeurism, colonialist impulses, and straight-up racism,” Wilson says of travel writing’s past, “it’s often not pretty.” And yet, there’s something of substance to putting time, thought, and effort into a genre that’s increasingly devoid of all three. Wilson wonders if the most “subversive, experimental, and honest” approach is actually to revamp the traditional first-person narrative. More and more, that’s my own goal, but I’ll add that the lens of the genre needs updating. Wagashi was a bittersweet reminder of this: that boundaries mean just as much as access, that a visitor is always a visitor.

Thank you for such a kind reading of my work!!